From Ground Zero: Gaza’s unbreakable spirit

Rashid Masharawi’s anthology of 22 short films, made from within Gaza under Israeli bombardment, shows the power of filmmaking in activism.

Ahmed Hassouna always dreamed of becoming a director. After studying journalism at Al-Azhar University in Gaza he began his filmmaking career, starting with documentary before moving onto his real dream: fiction. Written in chalk on Ahmed’s wooden clapperboard was “Istrupya”, meaning senseless loss, his first feature film. Whilst running a filmset, his life was a marathon. October 8th, 2023, the bombardment started. His life is now a different kind of marathon, running for food and firewood to keep his family safe and warm. When the firewood ran out, he had one option. His clapperboard. He tears it apart and throws it on the fire. “Sorry cinema”, he says, as the camera cuts and fades to black.

Sorry Cinema, by Ahmed Hassouna, is the third short film in From Ground Zero. An anthology made of twenty-two shorts created by filmmakers from within Gaza over 2024. Collated by Rashid Masharawi, it features a variety of genres from drama and comedy, to dance and stop-frame animation. It was released to international film festivals last year, notably headlining the London Palestine Film Festival in November. It’s also Palestine’s official entry into the 97th Academy Awards, and has now been shortlisted for Best International Film.

Rashid Masharawi is a Palestinian director, born in a Gaza. He is known for his 1994 film Curfew, which won the UNESCO Film Award at Cannes. As well as his charity The Masharawi Fund, which financially supports filmmakers in Gaza.

Rashid told me, “when this war started and I was in my research to select filmmakers from Gaza, I contacted Ahmed Hassouna… I told him ‘Ahmed, it’s your chance now. I’m going to produce a group of films from Gaza, I will show it all over the world in the most important places. You are in location now, join us. Make your film.’

“Ahmed said ‘no, I don’t want to make a film. I am fighting to save my life… I just lost my older brother. Rashid, sorry. I will tell you sorry and I will say sorry for the cinema, but I cannot make it.’

“I couldn’t pass it like this. I contacted him again, and say ‘listen Ahmed, you are going to make a film… We are going to make a film, that you don’t want to make a film… In the film tell me that you are in love with cinema, and now you cannot make a film because of this.’

“Today, Ahmed is shooting his next film with me, in Gaza.”

When speaking with Rashid, the pain in his words over the atrocities in Gaza is potent. He expressed his intention to raise awareness for these atrocities, through giving voice to Gaza’s culture.

“I always believe that to find a solution for the Palestinians, it cannot be from inside… The solution must come from outside, and from countries who could influence like America, like the UK.

“I don’t think we will push a button all will be solved.. We need all these initiatives and art, and culture, and paintings, and cinema, and theatre, and writing, and dancing... Because, this is our identity, and nobody can occupy identity.”

Now that the film is gaining more international prominence, with its American release in January, the reception has been unanimous about the film’s powerful nature. Publications like The New York Times and The Hollywood Reporter all giving it rave reviews.

Sarah Agha is an actor, writer and presenter of Palestinian/Irish decent. She starred in Film4’s Layla, as Fatima. She co-hosted BBC 2’s The Holy Land and Us, about Palestine in 1948. She created The Arab Film Club, a podcast which celebrates Arabic cinema and has sold out events at The Southbank Centre, The Glasgow Film Theatre, and Leicester Square’s The Prince Charles Cinema.

She says describing From Ground Zero: “What’s so powerful is the sheer fact that it was completed.

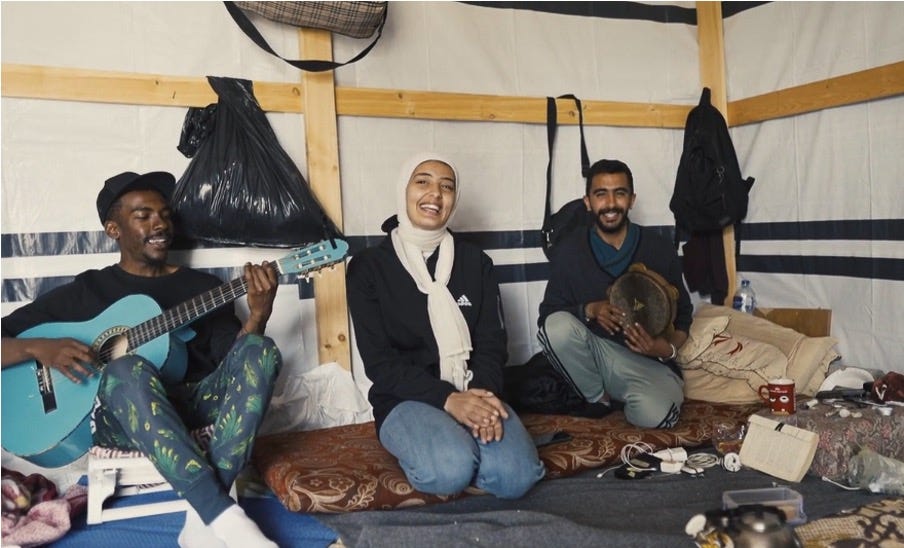

“It’s absolutely staggering to think that these people… are trying to find food for their family, are trying to survive, are trying to avoid being hit by bombs, are moving from one shelter to the next… and at the same time 22 films were made.

“Completing any film is often a miracle… So, the fact that these films were completed and to a high standard under bombardment, is such a testament to the strength and the resilience and the determination of the people living there.

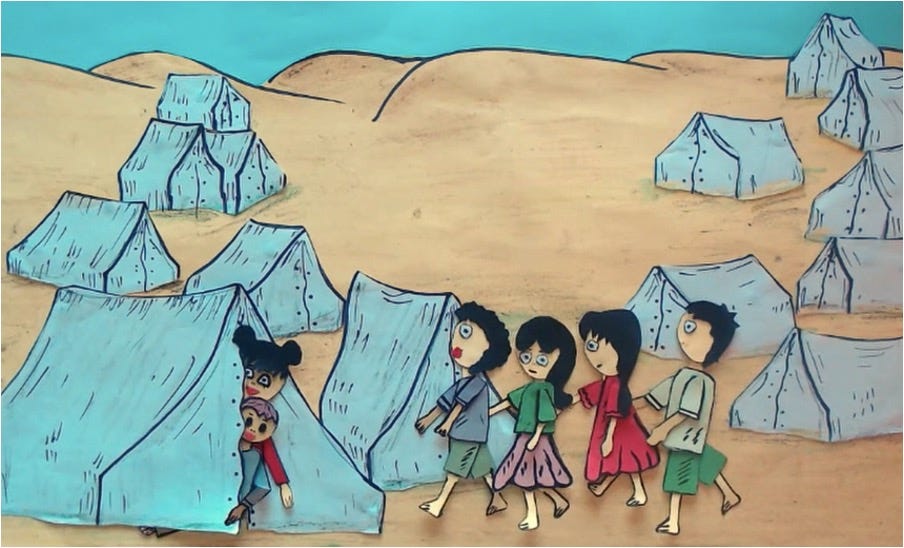

“I mean the animation, the idea that there’s animation made by children in tents. Stop motion animation of one of the hardest crafts out there.”

The film has a profound effect on a personal level, and can make for difficult viewing, but Sarah emphasises the importance of seeing it due its potential impact: “I found the content really quite upsetting. I’m half Palestinian. We’re all watching a genocide.

“When I watch a film or see a play its escapism, its storytelling, its characters… whereas this is something different. It’s certainly not escapism… I struggled to watch it, but I think it’s absolutely essential viewing.

“It’s a document that will be used all over the world for many years to come. It’s not just a dramatisation of an event. It’s evidence of what happened on the ground, of the victims and the survivors themselves.

“The film could have the impact… to encourage people to do everything in their might to make sure that this never happens again, but first and foremost to stop this.

“As British citizens, or American citizens, we are connected to it... we pay taxes to a government that is funding the war machine… We have a collective responsibility and duty to do all that we can to stop this and prevent it from happening in the future.”

Matt Robinson is a London based filmmaker and activist. In 2021, he won Best Director at the Virgin Spring Cinefest for Isolate, a film about loneliness. He also started Migration Films, an organisation which uses video to raise awareness for Gaza.

“To steer people’s mindsets, it’s the best way. Documentaries are for people who want to learn. Drama is for people that want to be entertained. And you can get to the masses more, I believe, through entertainment than through documentary.”

When asked about the power of the average person, he said: “Immense power… I do think turning up on the streets is important. I also believe that sharing on social media is very important… It’s evidence for the ICJ [International Court of Justice]. That’s what brought the ICCs [International Criminal Court] and ICJs was people sharing.

“Individually, we can all have an impact.”